Political reporting and punditry do a poor job in forecasting election results. Here is a closer look at how a political scientist would unpack the next elections.

The 2014 midterm elections are just a little more than a year away, but the prognostications have been flying for months about who will win, why, and how. Everyone has a story to sell about which party will pick up seats, and which campaigns are poised to do well and which ones are not. The problem is sorting the wheat from the chaff in these predictions.

Much of the political information on campaigns that is most readily available and easily digestible is biased. And when I use the term “biased,” I mean it in the true statistical sense. That is, the people writing about elections often want you to focus on a particular piece of evidence or a frame that validates their worldview about political outcomes. In short, much of the information about predicting political events begins not with a desire to really understand the political process but to sell a particular version of facts supporting their agenda. As a corrective, this piece will explain how political scientists think about forecasting congressional elections objectively — absent any agenda other than to understand the most likely outcome of those campaigns.

Politicians, pundits, and the press all carry baggage that makes them see the political world in a particular way. This clouds their objectivity when making predictions about an election. Politicians and party officials tend to be the worst in this regard. Take as an example the reaction to the announcement earlier this year of Montana Senator Max Baucus’ retirement — the long-time Democratic incumbent. Popular former Democratic Governor Brian Schweitzer was heavily recruited as his replacement. Then, to the surprise of many, myself included, Schweitzer chose not to enter the race.

This decision meant that the Democratic Party had just lost a top-tier challenger who had universal name recognition and was perhaps the best liked politician in the state. But Democratic officials continued to issue statements expressing confidence about holding the seat. The executive director of the party’s Senate campaign committee, Guy Cecil, noted that the “overall math still favors Democrats next year” and that “only three Democratic incumbents have lost reelection in the last decade.” Of course, this ignores the fact that the Montana Senate seat has no incumbent running for reelection. Meanwhile, the Montana State Democratic Party’s spokesperson Andrea Marcoccio said Democrats have held Baucus’ seat for more than 100 years and liked their odds of keeping it. That statement does not mean much given that Baucus has held the seat since 1978 and, before that, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, who won held it from 1952. Incumbents are hard to beat, and the Democratic Party and its labor allies were much stronger in the past than they are now.

To be sure, to some degree, we cannot expect parties to be interested in an objective account of the facts. They are designed to win elections. To do that, they have to rally the troops, keep them in line, and—above all else—make sure they are enthusiastic going into the election cycle. The information they disseminate about prospects in any given election should be taken, at best, with a grain of salt.

But political parties are not the only ones out there selling a story. The press and the political pundits on television can be just as bad. Journalists want to sell papers and get high Nielsen ratings—and to do it, they often focus on drama and controversy. Accordingly, they invest time and energy on the horse race in campaigns—who is up, who is down, and why—because it is entertaining, like watching an exciting pennant race. And just like the baseball scouts of old who often ascribed too much credence to a player’s batting stance or their presence on the field, journalists focus too much on the clash of candidates and the machinations of campaigns.

This is not to say campaigns do not matter, just that they matter much less than people think in the broad scheme of things. But journalists, who often “embed” in campaigns and spend much of their time observing them closely, have to believe they matter. Otherwise, what value is the access they have spent months obtaining or the information they have painstakingly gathered? Drama and unique access are commodities that reporters are selling when they tell you a campaign committed a mistake in the debate or made a fateful decision in the final weeks. The truth is that in most campaigns, the die was likely cast long before any “fatal flaw” emerged.

The same goes for pundits, who are interested in drawing your attention and building their own reputations—making them prone to outrageous predictions that are often useless in yielding accurate assessments. These pundits often live in the world of partisan politics and electioneering—making them just as prone to exaggerate the day-to-day campaign at the expense of the bigger political landscape. Nate Silver’s The Signal and the Noise notes that the political pundits that are so popular on television talks shows are in fact terrible and overconfident predictors. In fact, flipping a coin is more accurate than relying upon pundit predictions.

So can we objectively predict the outcome of elections in the aggregate? As a political scientist, I would begin with the electoral landscape, both past and present, and assess candidate recruitment, incumbency, and challenger quality. Only after those factors are taken into account do I consider the possible effect of campaigns on election outcomes. So let’s look at the next election – the 2014 mid-terms. Looking at those factors together, we see a dark picture for the prospects of the Democratic Party in retaining the Senate and capturing the House. Here’s how I come to that conclusion.

The Electoral Landscape

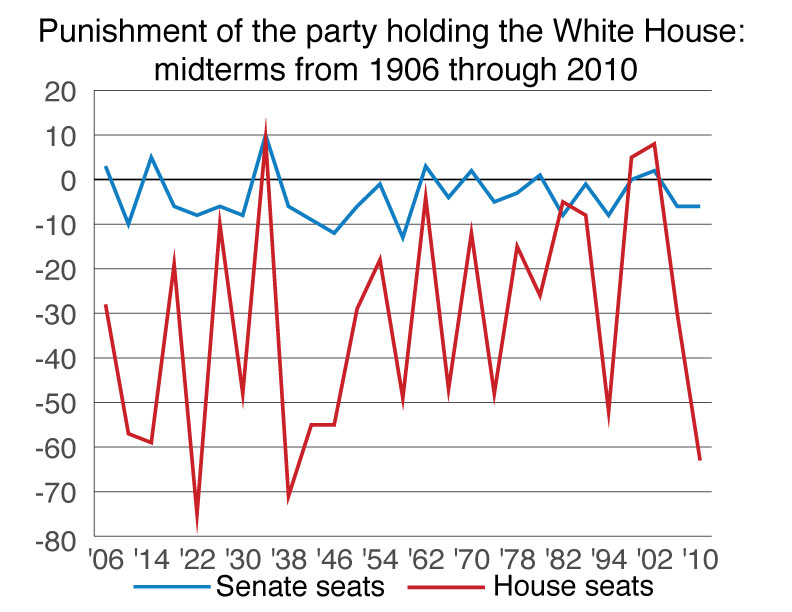

The electoral landscape does not bode well for the Democratic Party. First, it is important to remember that midterm elections are often a referendum on the incumbent party holding the White House. Since 1906, the party controlling the White House has lost congressional seats in every midterm election save three times: in 1934, 1998, and 2002.

On average, the party holding the White House has lost 32 House seats and nearly 4 Senate seats in a midterm election. Furthermore, the midterm electorates are very different from presidential-year electorates. As documented by David Wasserman at the Cook Political Report, voters participating in midterm elections have become older, whiter, and more Republican during the past decade, further cementing the fact that the Democrats are running into a stiff electoral wind that will make it nearly impossible to gain seats.

Two other factors are worth noting. First, when Republicans won control of the House in 2010, they also captured many governorships and state legislatures. This allowed them to dominate the decennial process of redistricting, giving them the edge in protecting vulnerable Republicans while making the lives of House Democrats even more difficult. This strength makes it even more unlikely that the Democrats will make inroads in the House. Two independent analyses — one by political scientists John Sides and Eric McGhee and the other by Sundeep Iyer at the Brennan Center for Justice — estimate redistricting perhaps helped Republicans protect six or seven Republican seats that otherwise would have been vulnerable in 2012. Second, the number of House seats that are true “swing” districts has been in decline since the 1970s, leaving fewer targets of opportunity for Democrats to pick off vulnerable Republican incumbents. Nearly all Republicans and Democrats in the House represent districts carried by their co-partisan presidential nominees—again there are very few truly competitive seats up for grabs. For Democrats to win back the House – a net gain of 17 seats — they would have to sweep all of the competitive seats, and then some.

Since only a third of Senate seats are up in any given election cycle, it is also important to look at the mix of those seats going into an election year. Because Democrats effectively picked up nine seats in 2008 to solidify their control of the Senate, they are now overexposed going into the 2014, with more seats to defend. Republicans are defending 14 seats, while the Democrats have to defend 21 seats. Worse for Democrats, only one Republican Senate seat is in a state where the Cook Report’s “Partisan Voting Index”—a measure scoring partisan tendencies in a state based upon presidential vote—favors Democrats. That is the Maine Senate seat held by moderate Republican Susan Collins, who happens to be very popular. Democrats, on the other hand, must defend six seats where the Partisan Voting Index favors Republicans: Alaska, Montana, South Dakota, Arkansas, Louisiana and West Virginia.

Clearly, the overall electoral landscape favors Republicans going into the cycle.

Recruitment, Incumbency, and Quality Candidates

It is hard to beat an incumbent. Senate incumbents win more than 85 percent of the time, while House incumbents more than 95 percent of the time when they run for reelection. And when an incumbent does lose, he or she generally represents a state that is out of step with them politically. In other cases, they have supported unpopular legislation or engaged in ethically dubious behavior. Because incumbents are so hard to beat, the name of the pick-up seats game is to look for open seat opportunities. At this point in the House, there will be 13 open seats—five Democrats and 8 Republicans are retiring or running for higher office. There does not seem to be any pattern in these retirements that would favor either party at this time, so this is a wash. Retirements will likely increase in the next year, but so far there is no rash of retirements that would produce a bunch of open seats in the House like there was in 1994. (And for the record, most of these House retirements in 1994 led to Republican pick-ups.

Retirements in the Senate, however, are a different story. In three of the most competitive Senate seats, longtime Democratic incumbents are retiring: Max Baucus, Tim Johnson (D-SD), and Jay Rockefeller (D-WV). In none of the three instances have Democrats found a strong candidate to replace them. Only in Georgia, where incumbent Republican Saxby Chambliss is retiring, do the Democrats have a chance of picking up an open seat. In the 2008 general election, Chambliss was held to under 50 percent and polled only three percentage points higher than his Democratic opponent. But in the ensuing run-off required under Georgia law, Chambliss crushed the Democratic Party nominee with 59 percent, suggesting that Republican-trending Georgia will be a very tough nut for the Democrats to crack in 2014.

It is important to note that candidate recruitment is an early signal of a party’s prospects. Good candidates think strategically and consider things like the electoral landscape, historic election returns, the economy, and presidential approval when deciding whether to make a run for higher office. Given how hard it has been for Senate Democrats to field candidates in open seat races like Montana—where every statewide office holder and the former popular Democratic governor all passed on the race—we have a sense of how difficult these strategic-minded candidates believe the 2014 cycle will be for the Democratic Party. As the old adage goes, you can’t beat somebody with nobody, and it will be hard for Democrats to take out Republican incumbents with candidates who have thin resumes and have never run for political office. The best candidates are those who have experience running successfully for office. Amateurs, more often than not, run losing campaigns.

The Campaigns

The final piece of the equation is the campaigns themselves. In many races, they will not matter because the incumbent represents a district that is overwhelmingly Democratic or Republican. The campaigns that will matter are in the few competitive and marginal House and Senate seats remaining. Good campaigns raise sufficient sums of money so they can execute their plans. In House seats, this often means raising and spending $3 million to $4 million. For Senate seats, a successful campaign often costs upwards of $10 million to $20 million. Without money, it is virtually impossible for a campaign to be successful.

To assess a candidate’s ability to do well, you have to begin with their fundraising efforts. If a candidate has amassed a strong war chest, chances are they will have the resources to conduct the campaign they want. But challenger fundraising is far more important than incumbent fundraising. Incumbents often raise and spend more than challengers because they are already well known, whereas challengers have to work harder to raise enough cash to become competitive. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, House challengers who raised and spent more than $2 million in 2012 had even odds of beating the incumbent. Under $1 million, the odds loom to almost 150 to 1.

Campaigns also matter because of the narratives they tell voters. Good narratives can persuade voters to vote against their partisan inclinations—and so can bad narratives. In the 2012 Senate race between Rep. Denny Rehberg (R) and Sen. Jon Tester (D) in Montana, the Tester campaign focused their early advertising on the positive, personal qualities of Jon Tester the farmer. They stressed his work on the family farm, his connection to Montanans, and his willingness to cross party lines to get work done. Rehberg, on the other hand, never established a compelling positive narrative about himself for Montanans to hold on to—a mistake that was critical in the fall when Democrats, outside groups, and the Tester campaign painted him as an individual more concerned with enriching himself than serving the public. In the end, Montanans voted for the candidate they felt had a stronger connection to them—even if that same candidate, Tester, may have represented a party different from their own. Campaigns matter, but they matter almost solely in close races—which, in 2014, will be few and far between. There will be a few surprises in 2014, but history suggests those surprises should benefit Republicans and not Democrats.

2014 Prognosis

I make two predictions based upon the historical record. First, Democrats will not only fail to regain the House but they will lose seats—probably in the range of 5 to 15. Second, they will not lose the Senate, but will shed as many as five seats, leaving their majority razor thin. There is absolutely nothing that suggests 2014 will break the historical pattern in the way that the elections of 1934, 1998, and 2002 did. Those cases were exceptions to the general midterm rule because of unique circumstances. In 1934, in the depths of the Great Depression, Democrats solidified their Senate and House majorities after an unusually aggressive legislative flurry that built the cornerstone of the New Deal. In 1998, Republicans lost seats amid the messy impeachment attempt of President Bill Clinton, who was personally popular and presiding over a booming economy. And in 2002, Republicans picked up seats in Congress and regained control of the Senate in an election that turned on national security a little more than a year following the 9/11 attacks. Barring unforeseen circumstances such as these, the 2014 midterms should continue to punish the party holding the White House in favor of the minority party—in this case, the Republicans.