This past September, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman announced that 19 companies in his state had agreed to pay fines totaling $350,000 for commissioning and posting deceptive online reviews for their products and services. While none of these companies was a household name, and the fines paled in comparison to billion-dollar settlements recently announced involving the likes of BP and JP Morgan Chase, the story landed on the front page of The New York Times. Within 48 hours the story went viral, with most commentators suggesting that Schneiderman’s probe proved what they had long suspected—namely, that highly coveted four- and five-star ratings on sites like Yelp, Amazon, and Citysearch could be rigged with a little ingenuity and the help of “reputation-enhancement” firms with global networks of low-paid reviewers. In fact, this ethically dubious branch of modern marketing has become so common that it has even acquired a name in business circles: astroturfing.

A day after breaking the story, Times reporter David Streitfeld took to the newspaper’s “Bits” blog to process the “voluminous response” he had received both online and in private. One particularly prevalent sentiment, he reported, was that this new phenomenon is bound to get worse before it gets better. “Sadly,” one reader lamented, “this is where ‘free-market’ capitalism is going. It’s not about creating a better product for the consumer, but about tricking consumers into thinking ‘yours’ is so much better than ‘theirs.’”

That so many gravitated toward such an interpretation is not altogether surprising — the original story invited readers to situate the astroturfing bust within a “decline of civilization” narrative. Midway through his article Streitfeld exchanged his reporter’s hat for that of the editorialist, writing, “Within recent memory, reviewing was something professionals did. The Internet changed that, letting anyone with a well-reasoned opinion or a half-baked attitude have his say.”

***

As compelling as this line of thought might initially be, it wilts when put to the historical test. What marketing theorists now call “astroturfing” was first dubbed “puffery” nearly 300 years ago and has remained one of advertising’s most effective tools ever since. The first widespread reports of puffery came in 1730s England, where a number of journalists and wits remarked on the recent shift from straightforward, unembellished announcements of goods for sale to elaborate schemes to trick consumers into buying shoddy merchandise.

Two trades in particular were seen as the foremost practitioners of puffery: quack medicines and books. In fact, the first known commercial usage of the term “puff” (the May 27, 1732 issue of London’s Weekly Register) pinned the practice squarely on booksellers: “Puff is become a cant Word to signify the Applause that Writers or Booksellers give to what they write or publish, in Order to increase its Reputation and Sale.” In 1740, Henry Fielding complained that impatience for literary fame “hath given Rise to several Inventions among Authors, to get themselves and their Works a Name. And has introduc’d that famous Art called Puffing, which [has been] brought to great Perfection in this Age.”

Two years later, Fielding penned one of literary history’s greatest exposés on puffery, the satirical novel Shamela, which mercilessly parodies the shameless promotional tactics that Samuel Richardson had recently employed to make his novel Pamela an international bestseller. Playing on Richardson’s predilection for loading each successive edition of Pamela with new “objective testimonials” to the novel’s greatness, Shamela begins with a panegyrical letter from “the editor to himself,” a panting endorsement from “John Puff, Esq.,” and a promise to preface future editions with further “commendatory letters” and spontaneous verses in praise of the author.

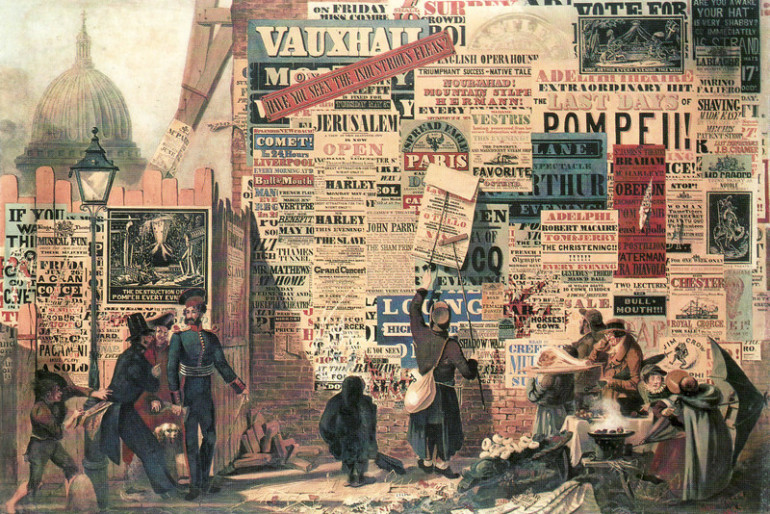

In many respects, the age of Fielding and Richardson is a remarkable analog to our own. Just as we grapple with the information overload resulting from the explosion of new media, these writers and their contemporaries were frequently bewildered by the new mores, codes, and ethics of the first great age of print. And just as many now are quick to blame the Internet for the rise of “astroturfing,” several eighteenth-century commentators saw puffery as the direct outgrowth of print culture. Samuel Johnson was particularly incisive on this issue, writing in 1759, “Advertisements are now so numerous that they are very negligently perused, and it is therefore become necessary to gain attention by magnificence of promises, and by eloquence sometimes sublime and sometimes pathetic.”

Then, as now, the challenge was figuring out a way to guide potential customers toward your product in a marketplace featuring a dizzying range of choices. Direct advertising had its place, but, like today’s Web surfers, eighteenth-century readers were becoming increasingly habituated to deflecting their gaze from the ads that popped up at every turn. For the first time, a printing network was publishing more noteworthy books, magazines, and newspapers than any reader could possibly consume, and a surging publishing industry quickly became desperate for new ways to advertise its wares. Facing this challenge, London publisher Ralph Griffiths devised one of the great inventions of modern literary and advertising history: the book review.

In 1749, Griffiths launched the Monthly Review, a periodical that promised to review every new book issuing forth from the nation’s presses and guide readers toward those titles that were most deserving of their attention. Although Griffiths initially pledged to keep the Monthly untainted by advertising, he quickly recognized that, while providing a genuine service to readers, his periodical could work wonders in directing book-buyers specifically to his own firm’s publications. In short order, nearly every issue contained glowing reviews of new books from the house of Griffith, many of them penned by the publisher himself. When Griffiths himself was too busy to puff his firm’s books, he granted authors themselves this privilege. Hiding behind the veil of the anonymous reviewer, John Cleland (of Fanny Hill fame) reviewed his own The Case of the Unfortunate Bosavern Penlez; Tobias Smollett encouraged readers to purchase a new book on midwifery that he himself edited; and John Hill hailed his own Adventures of Mr. Loveill as a tale possessing “a spirit and fire thro’ the whole that few performances of this kind have had a boast of.”

In short, from the very beginning, the professional book review was a compromised form. And things only got worse in the century to come. The fierce competition among publishers, the lure of huge potential paydays for successful authors, and the chummy relationship among writers, publishers, and reviewers in literary London all led to an explosion of insider reviewing. Reporting from London back to his native land in 1822, the American nationalist James Kirke Paulding claimed that nine of 10 reviews in British periodicals “originate in personal, political, and religious antipathies or attachments” and “it is almost as common for an author to puff his own book in the magazines, as for a quack doctor to be his own trumpeter in the newspapers.”

While the Anglophobic Paulding hardly counts as an objective source, his observations are only slightly exaggerated. Nearly every British writer of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries either participated in or benefitted from ginned-up book reviews. Mary Wollstonecraft reviewed her own translation of a French book in the Analytical Review. The future poet laureate, Robert Southey, only half-jestingly implored his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “Puff me, Coleridge! If you love me, puff me! Puff a couple of hundreds into my pocket!” And in an 1817 issue of the Quarterly Review, Walter Scott anonymously reviewed his own Tales of My Landlord, slyly noting “none have been more ready than ourselves to offer our applause.”

Other famous Romantic-era puffers included William Hazlitt, who lauded his own Characters of Shakespear’s Plays in the Edinburgh Review; Percy Shelley, who wrote a glowing (but ultimately unpublished) review of his wife’s Frankenstein for the Examiner; and Mary Shelley, who attempted to revive the reputation of her father, William Godwin, by puffing his novel Cloudesley in Blackwood’s Magazine. Even the great poet of rural simplicity, William Wordsworth, got into the act. When his friend Robert Southey published an unexpectedly even-handed review in 1798 of Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads, the poet ranted, “He knew that money was of importance to me. If he could not conscientiously have spoken differently of the volume, in common delicacy he ought to have declined the task of reviewing it.” Sixteen years later, when another friend’s review of Wordsworth’s poetry got severely rewritten prior to publication, the poet’s sister, Dorothy, sniped that one ought “never to employ a friend to review a Book unless he has the full command of the Review.”

***

For a modern reader looking at the puffery of the literary past, there is the temptation to 1) dismiss the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century book review as little more than a vehicle for disguised advertising, and 2) congratulate ourselves on the fact that we have largely cleansed the literary temple of such abuses. Further reflection on the first point, though, might remind us that, however susceptible to puffery these tight-knit literary circles of past ages were, much of the most insightful, sophisticated, and dazzling prose they produced came in the form of review essays, many of which were models of what Matthew Arnold famously dubbed “critical disinterestedness.” And on the second point, it requires only a simple Google search of “self-reviewing” or “fake reviews” to realize that literary puffery might be every bit as prevalent today as it was in the age of Fielding, Wollstonecraft, and Scott.

Although one can still find tough-minded, discriminating reviews in venues like the Times Literary Supplement, the New York Review of Books, and leading newspapers, there are countless recent cases of authors, publishers, and friends of authors being caught red-handed in the act of puffery. In 2004, for instance, when a glitch in Amazon’s Canadian website temporarily revealed the identities of hitherto anonymous reviewers, we learned that such luminaries as Dave Eggers, John Rechy, and Jonathan Franzen had uploaded five-star reviews for their own books or those by friends. In an even more sensational report, The New York Times recently profiled Todd Rutherford, the entrepreneur behind GettingBookReviews.com, a site that offered to post 20 online book reviews for $499 and 50 for $999.

As egregious as such cases might be, most modern literary puffery falls into an ethical gray area, where the offense of posting a trumped-up review is mitigated by its origin in a benevolent desire to support friends and colleagues. Whether ethically justifiable or not, however, this impulse has spawned a review and blurb culture in which famous writers and scholars strive to reach ever new hyperbolical heights in applauding new titles. Remarking on this trend, Jeffrey R. Gray recently marveled that there are no longer “minor poets” living in America: “William Bronk’s poetry, for example, ‘holds a unique place in the history of American letters.’ Kay Ryan ‘is one of the most original voices in contemporary American poetry.’” In a similar spirit, this past September, Edmund Gordon began his review of Colum McCann’s TransAtlantic in the London Review of Books by noting how McCann has become “the high priest of high praise, always handy with a blessing.” Gordon notes how “McCann has described Jim Crace as ‘quite simply, one of the great writers of our time,’ Aleksandar Hemon as ‘quite frankly, the greatest writer of our generation,’ and Nathan Englander as ‘quite simply, one of the very best we have.’”

Attempting to counter-balance this trend, the site The Omnivore recently began honoring the “Hatchet Job of the Year.” Justifying the establishment of this prize, its creator, Anna Baddeley, argues, “There aren’t enough negative reviews—reviewers are too deferential a lot of the time, and it leads to a problem of trust, because the reader gets forgotten.” Geoff Dyer, a nominee for the first Hatchet Job award, echoes Baddeley’s call for a higher standard in criticism, including stronger taboos against reviewing friends. “There’s that old joke,” he explains, “if you review books by your friends, you get to the point where you’re either not a very good critic, or you end up with few friends.”

***

Of course, it’s not just high-end literary publishing where puffery continues to hold sway. Academic book reviews can be every bit as glad-handing and hyperbolic. Unlike in the world of major publishing, however, in scholarly circles the primary incentive for puffery has less to do with commercial motives (given how small the sales are of even the most warmly praised academic titles) and more with building goodwill in one’s scholarly community. From a certain perspective, academic puffery is largely defensive, a natural behavior in tightly-knit academic sub-disciplines where there is much more to be lost than gained by trashing a new title, regardless of how short on merit the book might be. Especially for junior scholars, who increasingly write the lion’s share of academic book reviews, even the most knowledgeable and brilliantly argued critique can do more to alienate influential scholars and their allies than establish a reputation for deep learning and critical insight.

How, then, to enforce a higher standard in academic book reviewing? A general impulse to pull back, reassess, and invent new models is healthy. A few suggestions for starters:

First, create an ethic that makes reviewing the work of a close friend a clear breach of academic protocols, taboo along the same lines as plagiarism. Obviously, in many cases the best reviewer of a particular work will be someone who has long worked alongside the author in his or her field. But, for the sake of reviewing integrity, the Modern Language Association, American Historical Association, and other professional organizations for “book disciplines” should articulate standards outlining when it is and is not acceptable to review a colleague’s book. These documents could then become standard texts in graduate seminars and methods courses in the relevant fields.

Second, establish a standard practice in which journals clearly express the tone and level of critique they expect in book reviews. In many fields, there is currently a “one-size-fits-all” approach, in which reviewers receive no journal-specific instructions (other than about length and citation style), and there is a general assumption that all journals expect the same basic thing. Given the widely divergent opinions among academics, however, about what the ideal review should accomplish, reviewers and readers alike would benefit from explicit statements about the journal’s attitudes. For instance, some academics believe that the ideal review should summarize the book’s aims and, in a spirit of generosity, highlight what it adds to the field. Others want an expert’s opinion on where a new book succeeds, where it falls short, and, dust-jacket blurbs aside, just how significant a contribution it makes to the field. There is certainly room for both styles of review, but it would require much less suspicion and between-the-lines reading on the part of the reader if he or she knew whether a particular journal had a policy of featuring either “accentuate the positive” or “warts and all” reviews.

Third, our new digital age should ideally facilitate radical new approaches to reviewing. Some sites might feature new twists on old debates (e.g., experimenting once again with anonymous reviewing) or more civil versions of the comments section featured in many newspaper and magazine websites. In the spirit of dialogue rather than defensiveness, the practice of authors responding to reviewers could become the norm rather than a right exercised only in the face of particularly mean-spirited or libelous reviews. Such practices are already being experimented with at sites like Review 19, but more often than not reviewers fall back into old habits rather than embracing the potentially disruptive new genre.

Finally, in a world where at least half of academic books are at one point or another named a “must-read” for students and scholars in the field, more reviewing venues might follow the lead of the website CHOICE in producing a year-end list of “Outstanding Titles” that includes no more than 10 percent of the books reviewed over the course of the year. Obviously, this might open up yet another avenue for puffery, but if journal editors embraced an ethic in which puffery were as offensive as plagiarism, they might burnish their credentials for fairness by refusing to consider books published by members of the editorial board.

All of this is just a beginning, but if we’re sincerely dedicated to open, rigorous exchange, we need to enforce the same protocols in academic reviewing that we would expect in consumer and literary reviews. If these suggestions sound too daunting, we must remember that the industry has the capability to self-correct – and has done so before. In the 1820s and 1830s, when literary Britain had finally had enough of empty and deceptive reviews, an unofficial consortium of authors, critics, and editors came together to suggest new standards for reviewing. As a first step, they began naming names—publishing detailed lists of authors suspected of “buttering” their own or their friends’ works. They also experimented with what we would call “open review,” in which journals began publishing the names of reviewers. More than anything, this consortium united around the slogan of “critical independence,” building theoretically impermeable barriers between review periodicals and the book industry. We do not need to take every page from this playbook, but with the enormous transformations currently underway in publishing, the moment is right for a second great reformation in literary and academic reviewing.